In the weeks leading up to Bangladesh’s February 12 general election, the Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami projected unusual confidence. Political analysts in Dhaka speculated that the party long relegated to the margins of national politics might record its strongest electoral performance since independence. With the Awami League banned from contesting and the political landscape dramatically reshaped by the 2024 uprising, Jamaat sensed an opening.

Yet as results unfolded, the momentum shifted decisively elsewhere. The Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), led by Tarique Rahman, declared victory, and congratulatory messages from foreign missions quickly followed. Jamaat, in contrast, issued a cautious statement expressing “serious questions about the integrity of the results process,” even as official tallies were still being compiled.

The outcome marked a sharp reversal for a party that had entered the race believing it had both organisational energy and political space on its side.

Early Street Credibility, Limited Electoral Conversion

In the aftermath of the July 2024 student-led uprising that toppled the Awami League government, Jamaat was widely viewed as one of the beneficiaries of political realignment. The party had been active in protest mobilisation, positioning itself as part of the anti-incumbency wave that ended Sheikh Hasina’s tenure.

With the Awami League out of the electoral picture, the contest narrowed significantly. For the first time in years, Jamaat was not contesting in the shadow of a dominant ruling party. Moreover, Tarique Rahman’s formal entry into the race came relatively late, giving Jamaat temporary breathing room in several constituencies.

But as campaigning intensified, the BNP’s national machinery accelerated. Rahman’s return galvanised supporters, and the party consolidated anti-Awami sentiment far more effectively than Jamaat.

Voter behaviour revealed a decisive trend. Young Bangladeshis many of whom had driven the 2024 protests gravitated toward the BNP rather than Jamaat. Women voters did not shift in significant numbers toward Jamaat’s rebranded platform. Minority communities, particularly Hindus, overwhelmingly backed the BNP. Even Awami League voters who participated chose the BNP as the principal alternative.

The result was clear: Jamaat’s early street momentum did not translate into a broad-based electoral coalition.

Diplomatic Engagement and Political Optics

Jamaat’s campaign was further complicated by international attention. A report by The Washington Post cited audio recordings suggesting increased engagement between American diplomats and Jamaat leaders. According to the report, outreach included discussions that appeared to downplay concerns about the party’s hardline reputation.

The optics of that engagement became politically sensitive. BNP Secretary General Mirza Fakhrul Islam Alamgir publicly alleged that Jamaat had struck a quiet understanding with the United States a charge Jamaat did not confirm. The party described meetings with Western envoys as routine pre-election consultations focused on democratic processes.

Still, the narrative fed into domestic suspicions. In an election shaped by nationalism and sovereignty concerns, even the perception of foreign alignment carried risks.

A Difficult Legacy to Reframe

Jamaat’s deeper challenge lay in history.

Founded in 1941 by Islamic scholar Syed Abul Ala Maududi, the party opposed Bangladesh’s independence in 1971 and sided with West Pakistan during the Liberation War. Paramilitary groups linked to Jamaat figures were accused of atrocities, including targeting civilians and minority communities. After independence, the party was banned before re-entering politics in 1979.

Under Sheikh Hasina’s government, several Jamaat leaders were prosecuted by the International Crimes Tribunal. High-profile executions and the cancellation of the party’s registration in 2013 left Jamaat politically isolated for more than a decade.

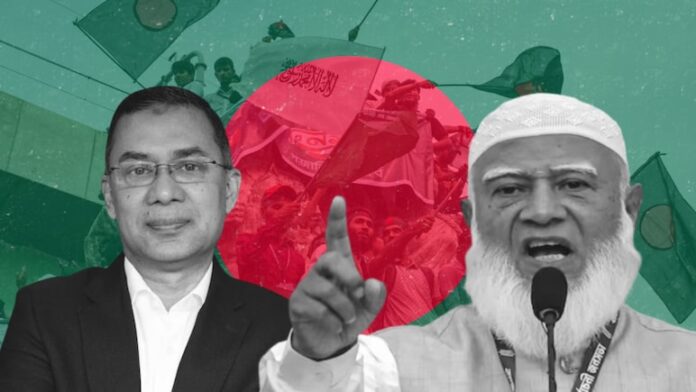

Following the 2024 uprising, Jamaat attempted a strategic repositioning. It framed itself as “pro-Uprising” and “anti-fascist,” promoted minority rights rhetoric, and even fielded its first Hindu candidate. Party chief Shafiqur Rahman adopted inclusive language, speaking of gender partnership and justice-based governance.

However, rebranding proved difficult.

Public memory of Jamaat’s advocacy of Sharia-based laws, opposition to past women’s rights reforms, and allegations of political violence involving its student wing Islami Chhatra Shibir continued to influence perceptions. Concerns among minority communities remained pronounced.

While the party moderated tone, scepticism persisted over whether its ideological core had truly shifted.

Strategic Miscalculation

Jamaat also appeared to overestimate fragmentation within the opposition vote. Rather than splitting the anti-Awami electorate, the BNP succeeded in consolidating it. Rahman’s leadership provided a familiar and arguably less polarising alternative.

In campaign messaging, Jamaat sought to contrast itself with dynastic politics, arguing that a 10-party alliance under its leadership would represent “the people” rather than any family or single party. Yet that appeal struggled against the BNP’s established infrastructure and broader acceptability.

Ultimately, the election demonstrated that protest participation and ideological conviction do not automatically convert into electoral viability. Building a governing coalition requires trust across generational, gender, and religious lines areas where Jamaat’s credibility remains contested.

Looking Ahead

Jamaat’s post-election statement questioning the results process suggests the party is reassessing both tactics and terrain. But the broader lesson may lie not in procedural complaints, but in political arithmetic.

The 2026 election underscored that while the Awami League’s absence reshaped the battlefield, it did not guarantee Jamaat’s ascendancy. Historical memory, coalition dynamics, and voter caution collectively constrained its breakthrough moment.

For Jamaat-e-Islami, the challenge now is strategic: whether to continue softening its image and broaden appeal, or retreat to a more ideologically defined base.