China has begun construction of a dam which is expected to become the world’s largest hydropower dam. it will be situated deep in the Himalayas, on the Yarlung Tsangpo River. While Beijing promotes it as a milestone in clean energy, the project raises serious concerns for millions living downstream in India and Bangladesh. These concerns span water security, agriculture, and regional stability.

Location and Impact of China’s Brahmaputra Dam Project

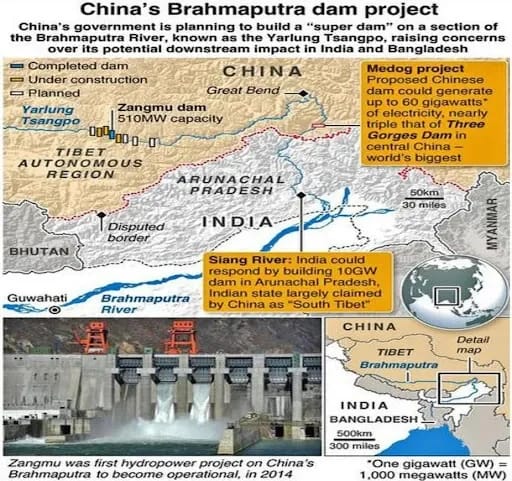

The dam is being built on the Yarlung Tsangpo river in Tibet, which becomes the Brahmaputra in India. The graphic shows how the project could affect water flow to India and Bangladesh, and India’s planned response in Arunachal Pradesh.

A Super Dam in a Super Canyon

The dam is located in Medog County, Tibet Autonomous Region, where the Yarlung Tsangpo takes a dramatic turn known as the “Great Bend” around Namcha Barwa mountain. This is the world’s deepest canyon, with a river drop of nearly 2,000 meters—ideal for generating massive hydropower.

The planned structure—called the Motuo Hydropower Station. It will have a capacity of 60 gigawatts (GW), nearly three times that of China’s Three Gorges Dam. When completed, it could generate 300 billion kilowatt-hours of electricity every year. According to Chinese officials, the project will bring in $3 billion annually for Tibet. It is going to be part of China’s larger “West-to-East electricity transfer” policy.

This dam is one of the biggest infrastructure projects in China’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021–2025) and is aligned with Beijing’s pledge to achieve carbon neutrality by 2060.

Strategic Location, Strategic Consequences

The Yarlung Tsangpo River becomes the Siang River in Arunachal Pradesh and then the Brahmaputra in Assam, before entering Bangladesh as the Jamuna River. Any change in its natural flow directly impacts millions of people in these countries.

India’s main concerns include:

-

Water Security: Experts warn that the dam may reduce water flow to India during dry seasons and release excess water during monsoons, risking floods in Assam and Arunachal Pradesh.

-

Agriculture: Silt carried by the Brahmaputra is vital for the fertility of farmlands in Assam. The dam may trap this silt, reducing soil productivity.

-

Strategic Risk: During the 2017 Doklam standoff, China withheld river flow data. This raised fears that Beijing could weaponize water during future border tensions.

Bangladesh has also raised concerns. In February, Dhaka formally requested more information from China, fearing disruptions to agriculture, fisheries, and livelihoods.

The Environment and People at Risk

China claims the dam is a run-of-the-river project, meaning it won’t store large amounts of water. But critics say the impact could be far greater.

Environmentalists worry about:

-

Seismic Risks: The Himalayan region is prone to earthquakes. A mega-dam in such a zone could be dangerous.

-

Ecosystem Disruption: The region hosts endangered species and fragile ecosystems. Flooding of valleys could cause irreversible biodiversity loss.

-

Local Communities: Many indigenous Tibetans have protested against past dams. In 2023, hundreds were reportedly detained during demonstrations against a similar project. Human rights groups say these infrastructure projects often come with forced displacement and lack of consultation.

India’s Counterplans

India’s Plans are underway to build a 10 GW hydropower dam in Arunachal Pradesh’s Dibang Valley, which will serve as a buffer against China’s dam. The idea is to stabilize river flow and protect Indian territory from sudden water surges.

India has also emphasized data-sharing under the 2006 Expert Level Mechanism (ELM) for trans-border rivers. However, cooperation has been inconsistent, especially during times of diplomatic tension.

In January, India’s Ministry of External Affairs officially raised concerns with Beijing and called for greater transparency and consultation with downstream nations.

Arunachal Pradesh Chief Minister Pema Khandu voiced alarm, saying the project poses an “existential threat” to local tribes like the Adi.

“If China suddenly releases water, the entire Siang belt could be wiped out,” he warned.

A Broader Power Play

The $137 billion dam is more than an energy project. It’s part of a larger geopolitical strategy. A 2020 report by Australia’s Lowy Institute noted that

“control over rivers on the Tibetan Plateau gives China a potential chokehold on India’s economy.”

In effect, the control of water especially in Asia, is becoming a new frontier in strategic competition, much like oil was in the 20th century.

While Beijing argues that the project will reduce pollution and help develop Tibet, its downstream neighbors fear they are being left out of critical conversations that could determine their future.

China’s Brahmaputra dam may represent technological ambition and renewable energy progress. But it also highlights a lack of multilateral governance when it comes to transboundary rivers.

For India and Bangladesh, the challenge now is to balance diplomacy with preparedness—securing water rights while building defensive infrastructure at home. For China, this is a test of how a rising global power engages with its neighbors on shared natural resources.